READER: RASCH

23.07.2025

Sebastian Claren: Hear Your Brother Hear II (1998/2025)

für Violoncello solo / for Violoncello solo

Uraufführung der Neufassung / World Premiere of the new version

Yu Kuwabara: Nokorigaku (Remaining Music) (2019)

für Klavier solo / for Piano solo

Helena Tulve: To Night-Travellers, the Light… (2009/18)

für Violoncello und Klavier / for Violoncello and Piano

Evan Johnson: A fountain (2024)

für Klavier solo / for Piano solo

Deutsche Erstaufführung / German Premiere

Brice Pauset: Rasch (2006/25)

Nr. 1, 2b, 3

für Violoncello solo / for Violoncello solo

Uraufführung / World Premiere

Kompositionsauftrag von / Commissioned by Darmstädter Ferienkurse & Hepner Foundation

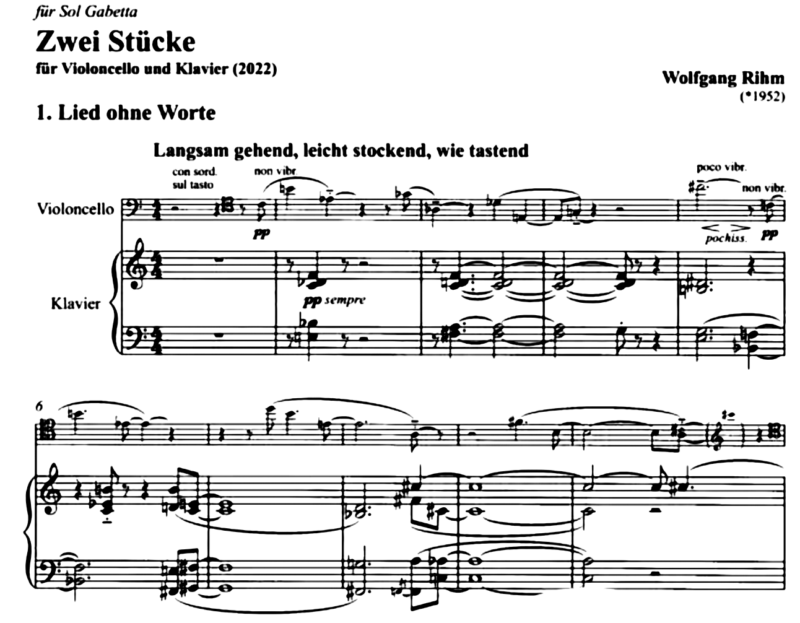

Wolfgang Rihm: Zwei Lieder ohne Worte (2022)

für Violoncello und Klavier / for Violoncello and Piano

– Langsam gehend, wie tastend

– Verschwundene Worte

Lucas Fels (Violoncello)

Nicolas Hodges (Klavier / Piano)

HEAR YOUR BROTHER HEAR II (1998/2025)

The first version of Hear Your Brother Hear was written for the Darmstadt Summer Course in 1998. I wrote the piece for a cellist friend of mine who was taking part in the course at the time. Lucas Fels, who was already responsible for the cello class at the time, turned me down: the piece was simply too difficult. Nevertheless, he showed interest and was prepared to work through the piece in detail.

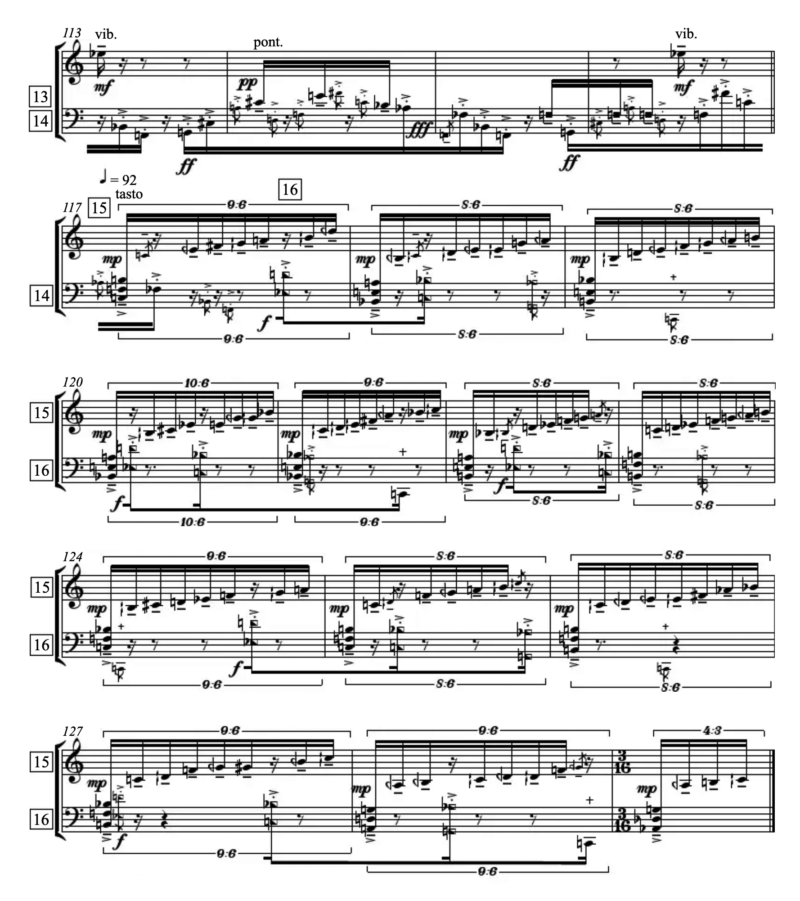

Lucas was absolutely right in his assessment – the score was unplayable in its original form. But that was part of the original idea. I wanted to push the technical demands as far as possible – not only to challenge the performers’ physical and interpretative limits, but above all to question the traditional concept of a solo piece. The typical linearity, i.e. the progression of a single musical line in time and space, was to be broken up. I imagined a cello that doubles or multiplies itself and enters into a musical dialog with itself.

A central impulse for this idea came from a perhaps unusual direction for new music: the Studio 1-Variationen by Thomas Brinkmann. These were released in 1997 on the Cologne techno label Profan and were based on extremely minimalist tracks by Wolfgang Voigt. Brinkmann played these pieces on a modified record player with two tonearms. The slightly offset scanning of the pickups created new rhythmic structures – almost like phase-shifted loops – which developed a fascinating depth and complexity through minimal differences. The idea that something completely new can be created from the simplest source material by doubling and shifting was very inspiring for me.

Hear Your Brother Hear is also strongly influenced by the club music of the 1990s. The musical allusions to genres such as drum ‘n’ bass and minimal techno are deliberately chosen – not as mere stylistic quotations, but as structural references. As in a DJ set, the piece consists of a limited number of clearly distinguishable materials that can appear individually or overlap. However, while DJs match the tempos of the tracks to each other when mixing, the individual layers of material in my piece always retain their own tempo – even if they sound at the same time. This results in complex rhythmic interactions that are not created by variation within a material, but rather by the juxtaposition of the different materials.

I have revised Hear Your Brother Hear several times over the years – no other composition of mine has gone through so many different versions. In 2012, Lucas finally played a version at Ultraschall Berlin in which I had made some simplifications: the meter was more legible, articulations were notated more clearly and the playing was technically much more accessible – but without abandoning the basic idea.

When in 2024 I suggested to take up the piece again, Lucas said that a revised version was needed. I took this as an opportunity not only to create another revision, but to deliberately give myself the freedom to make major changes. The resulting version therefore bears the title Hear Your Brother Hear II to signalize that it is no longer a mere continuation, but an independent new version.

Previously, the piece was always notated in several staves, similar to a piano score, in order to clearly separate the different musical layers. This made sense from a compositional point of view, but posed considerable challenges for the performers in terms of the legibility and imaginability of the musical structure. In Hear Your Brother Hear II, the entire material is now notated in a single system. I believe that this makes the original intention of breaking up the linearity of the solo playing even clearer. This is because the multi-layered nature becomes immediately perceptible – and the physical, mental and musical pressure that arises from the constant change between the levels can be grasped more precisely and realized more precisely.

Sebastian Claren, July 2025

NOKORIGAKU (Remaining Music)

Through my research, collaborations, and creations with traditional Japanese arts and music, I have discovered that sound is akin to energy and has the capacity to simultaneously bend and stretch, expand and contract. Traditional Japanese music is shaped through the dynamic interaction of sounds, each possessing its own inner motion and tension. My compositional process focuses on shaping and controlling the degree and gradation of this energetic quality.

One of the defining features of my earlier works is the use of “elastic” musical gestures, constructed from glissandi, quarter-tone combinations, exaggerated dynamics, and subtle textures. These gestures rely on the ability to shape sound continuously. In contrast, the piano is an instrument grounded in the chromatic scale, with each note producing a decaying sound unless extended techniques are employed. Moreover, for me, the piano represents the culmination of a long history of Western music – a perfectly completed instrument, but one that presents certain limitations. Writing for solo piano has never felt easy or straightforward.

When composing Nokorigaku, my first question was: how can I translate my own “elastic” gestures into a piano piece? This led to deeper inquiries – why do I rely on these gestures? What do they truly represent in my music? Do I even need them in this work?

A central concern in my recent compositions has been the question of “time.” In the past, I focused primarily on generating sound, allowing the form of a piece to emerge from the directionality and interrelation of sonic events. Recently, I’ve shifted my attention: instead of allowing sound to shape time, I now try to compose time itself – to shape musical time as an experiential structure, and treat sound as a component that defines that structure.

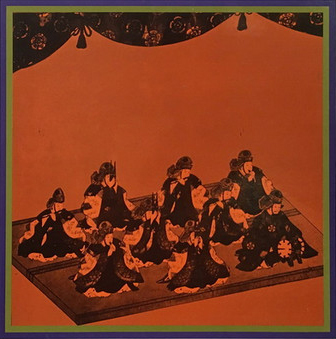

In this composition, I drew inspiration from the intricate form of the gagaku performance practice known as Nokorigaku (残楽), in which the ensemble gradually thins out over successive repetitions of a section. This idea of dissolution, of sonic subtraction, provided a framework for exploring time not through growth or expansion, but through reduction and vanishing presence.

Ju Kuwabara

For further reference regarding my aesthetic approach to time, texture, and elasticity in sound, here are two previous compositions that explore related ideas:

Search the Darkness

Sit with your friends, don’t go back to sleep.

Don’t sink like a fish to the bottom of the sea.

Surge like an ocean, don’t scatter yourself like a storm.

Life’s waters flow from darkness.

Search the darkness, don’t run from it.

Night travelers are full of light, and you are too:

don’t leave this companionship.

Be a wakeful candle in a golden dish,

don’t slip into the dirt like quicksilver.

The moon appears for night travelers,

be watchful when the moon is full.

TO NIGHT TRAVELLERS, THE LIGHT … (2009) for Violoncello and Piano

The work was inspired by a line from Rumi that stayed in my mind, and more broadly by nocturnal journeys – both in dreams and in waking life.

The piece is dedicated to my friend and teacher, Erkki-Sven Tüür.

Helena Tulve

A FOUNTAIN

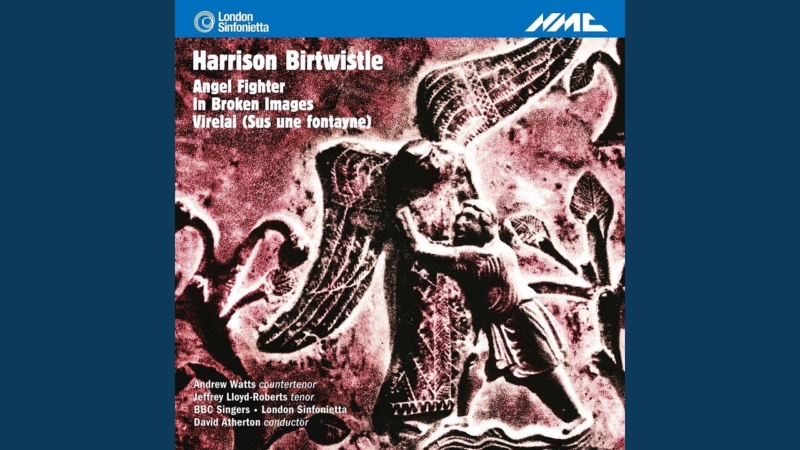

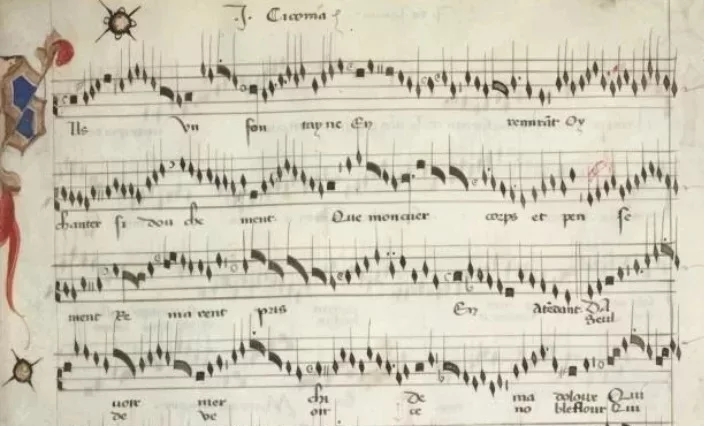

A fountain is a series of hoverings around Johannes Ciconia’s famous virelai Sus’ un fontayne. For the most part, though – aside from a few moments of clarity here and there that usually take the form of more or less isolated harmonies or scattered, lost fragments of scales or other bare melodic elements – those hoverings take place at a significant distance.

They also, despite their differences in length, rhetoric, energies, each take a similar form: an event occurs, and then stumblingly attempts to continue, to fend off evaporation.

This piece is dedicated in gratitude and admiration to Nicolas Hodges, with thanks for his interest in my work over the past decade, but the late Harrison Birtwistle is also hovering: a longtime friend and colleague of Hodges’, another transcriber of Sus’ un fontayne, and the great master of the struggle forward.

Evan Johnson

wikipedia "virelai"A virelai is a form of medieval French verse used often in poetry and music. It is one of the three formes fixes (the others were the ballade and the rondeau) and was one of the most common verse forms set to music in Europe from the late thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries.

Roland Barthes: Rasch, in "The Responsibility of Forms. Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Prepresentation. Translated from the French by Richard Howard.", pp. 299–312, 311."Rasch": this, say the publishers, signifies only: "quick", "fast (presto)". But I who am not German and who, confronted by this foreign tongue, possess only a stupefied listening, I add to it the truth of the signifier: as if I had a limb swept away, torn off by the wind, whipped toward a site of dispersion which is precise but unkown. In a famous text, Benveniste sets in opposition two realms of signification: the semiotic, an order of articulated signs each of which has a meaning (such as the natural language), and the semantic, an order of discourse no unit of which signifies in itself, although the ensemble is given a capacity for signifying. Music, Benveniste says, belongs to semantics (and not to semiotics), since sounds are not signs (no sound, in itself, has meaning); hence, Benveniste continues, music is a language which has a syntax but no semiotics. What Benveniste does not say, but what perhaps he would not contradict, is that musical signifying, in a much clearer fashion than linguistic signification, is steeped in desire. […] the syntax of the "Kreisleriana" is that of the quilt: the body, one might say, accumulates its expenditure – signifying takes on the frenzy but also the sovereignty of an economy which destroys itself as it develops; it therefore relates to a semanalysis, or one might say to a second semiology, that of the body in a state of music;

RASCH (Essay über künstlerische Intelligenz)

“In Schumann’s Kreisleriana, I actually hear no note, no theme, no contour, no grammar no meaning […]. No, what I hear are blows: I hear what beats in the body, what beats the body, or better: I hear this body that beats.”

Thus begins Roland Barthes’ text Rasch, which was written in 1975 in connection with an homage to Émile Benveniste. The question of the body, which plays a central role in my work, does indeed elude the whole range of possible, plausible and convenient traditional explanations. What is important here, in this cycle of pieces for cello, would be the ghostly appearance of the piano of the Kreisleriana (R.S.’s) through the mutation of the instrumental body, triggered solely by the words of others (R.B.’s).

Strictly speaking, it is an exercise in pure and strict analogy. We are here in Darmstadt, a meeting point of many of the currents that nourish the musical reflection of the present time. This cycle of cello pieces is certainly a modest and unremarkable object, but I want it to serve as a moment of meditation on what analogy means in relation to one of its counter-models, particularly AI. While analogy unfolds thought and liberates the realization of things in the concrete, robust, and elastic experience of subjectivity, AI reduces our thought, language and affects to stereotypes obtained through the averaging of the filtered and reified past. In this sense, it represents quite well the political ideas and underlying economic models that it supports and feeds on. I’m skipping over its environmental impact here, which for me is the central point of aporia for AI as a solution.

I come back to music: it is a familiar, almost banal experience: a friend tells us enthusiastically about the strong impression a piece of music made on him or her, and when listening to the same music, a phenomenon of recognition occurs: you literally “re-listen” to what you have never heard before, but already suspected. I would like to describe this experience of the impossible first hearing.

B.P., July 2025

ZWEI LIEDER OHNE WORTE (2022)

Wolfgang Rihm in conversation with Stefan Fricke and Bernd Künzig, musiktexte.online, October 2024 (https://www.musiktexte.online/ausgaben/10-2024/interview-wolfgang-rihm)It helps not to avoid it. I can't talk either, but I don't avoid it. I try again and again, and that gives the impression that I can do it. But it keeps slipping away from me. I'm constantly losing what I have to say, no longer recognizing what I want to say. I'm constantly losing the context. And talking about music is very important. That's why I mean: don't avoid it. But not to fall back into a stamped, prepared form of articulation, where an opinion, a this-is-so, a judgment from the outset, an a priori judgment is rampant without question. That is very difficult. I can't solve it either. There are so many people who call themselves philosophers, there are so many people who call themselves analysts, who are much better at it than I am. But of course they have no insight into the creative sphere. I can perhaps help them if I can give them an insight into this strange intermediate realm of forms, which means the creative, the promoting, the forcing, the requesting, the desiring action in a medium. I don't do things because I know from the outset that they are right and must be done, but I do them because I sense that there is an opportunity open to me to do something that doesn't exist in this form and that won't be available again so quickly.