READER: CORE

01.08.2025

Chaya Czernowin: The Divine Thawing of the Core (2024–25) – 60′

World Premiere

Claire Chase (Contrabass Flute)

Participants of the Darmstadt Summer Course

Vimbayi Kaziboni (Musical Direction)

Claire Chase (Contrabass Flute)

Participants of the Darmstadt Summer Course

Flute:

Ksenija Franeta

Isabelle Meraner

Seraina Ramseier

Łucja Chyrzyńska

Paschalia Digka

Snir Kaduri

Oboe:

Nai-Hua Chuang

Martín Zulaika Diarte

Sergey Khodyrev

Maya Kaya

Eric Aragó Bishop

Ella Dorothea Delbrück

Trumpet:

Monica Sanguedolce

Victor Vogel

Isaac Dubow

Jack Jones

Dmytro Zakaliuzhnyi

Paul Hübner (Gast / Guest)

Trombone:

Chloé Ryo

Tuba:

Fanny Meteier

Percussion:

Rita Sousa e Castro Couto Soares

Piano:

Shiori Yoshino

Violoncello:

Elizabeth Kate Hall-Keough

Jung In Kim

Liam Battle

Vimbayi Kaziboni (Musical Direction)

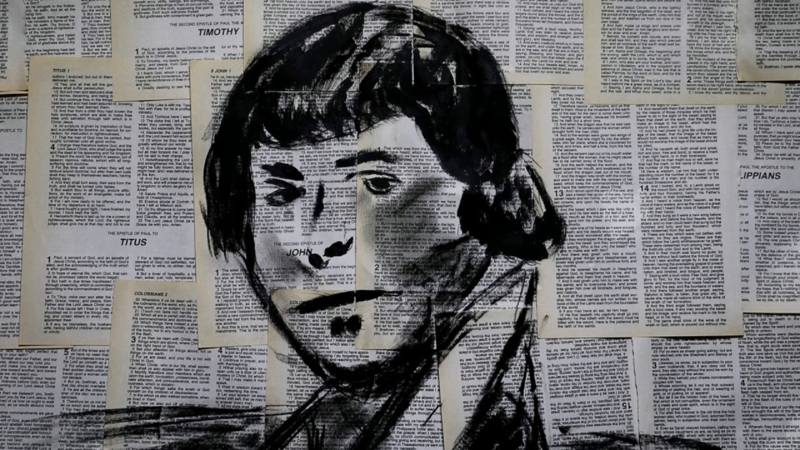

THE DIVINE THAWING OF THE CORE

The divine thawing of the core is a piece in a close formation to Galina Ustvolskaya’s Symphony No. 2. It is written for and dedicated to Claire Chase who initiated the piece some years ago. Claire will play the contrabass flute as soloist, with an orchestra of six flutes, six oboes, six trumpets, trombone, tuba, percussion, piano and three cellos. The piece will be premiered in July 2025 during the Darmstadt Summer Course, followed up by performances in August during Time Spans Festival in NYC and during Lucerne Festival in September. It is commissioned by these three festivals.

Ustvolskaya’s work has always been extremely important for me. I admire its courage and its directness and especially its capacity to unify the experience of sound and form. Especially important is the Symphony No. 2, a piece which must be experienced live when one would like to unlock its sonic luminosity and uniqueness. I therefore decided to offer a piece in a close formation to the 2nd Symphony with the hope, that this would also mean that Ustvolskaya’s piece might be played at the same concert. However, The divine thawing of the core may be played alone. The two pieces are not related further than the lineup.

The pairing of this orchestration with Claire Chase playing the contrabass flute were a strong guide for the piece. It is a very elemental, naked and maybe an intimate beginning, which is forced to melt away through irony into an elemental brutality, in an uneven process, which includes a demonic waltz, in a gradual thawing of its features into a kind of a wholly different way of expression which is more coherent, ceremonial and brutally primitive.

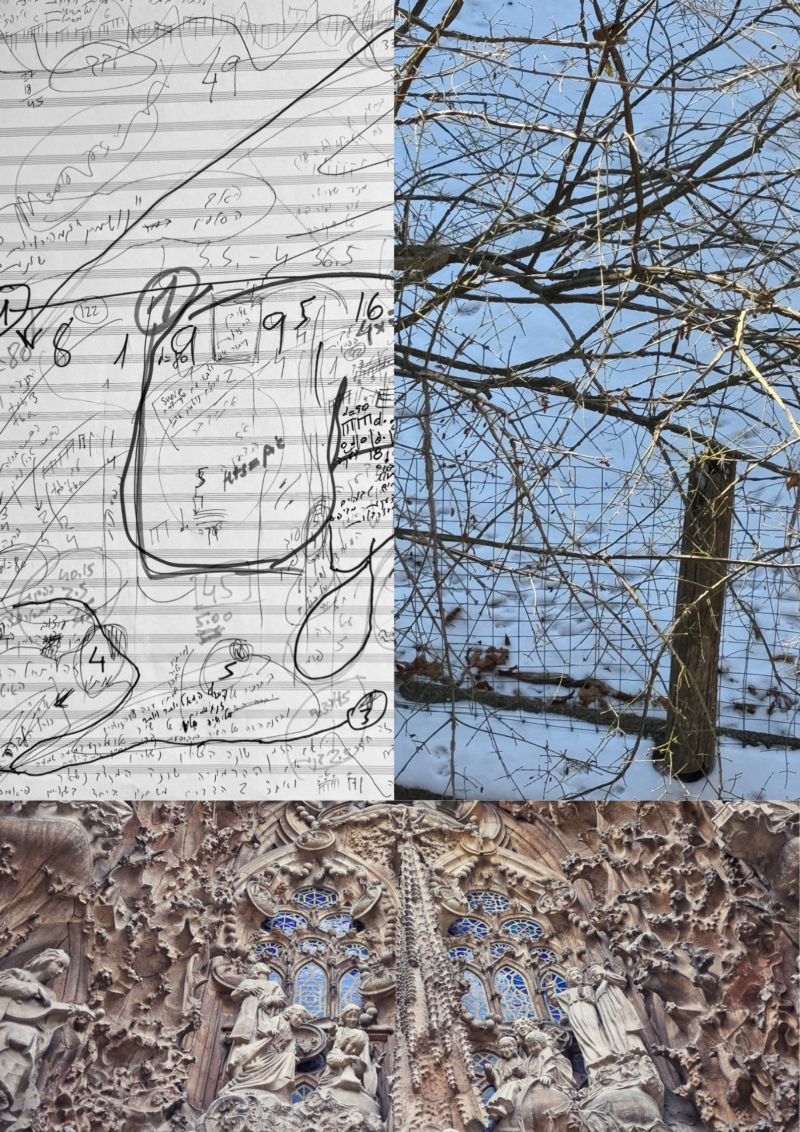

During the time of writing the piece I was in Barcelona and saw the Basilica de la Sagrada Familia. Seeing this strange and gnarly structure clarified for me the structure of this piece. It is unperiodically cyclical, the repetitions creating cavernous corridors and strange temporal illusions in the unfolding of the piece.

The title comes from observing the political process of the last difficult years, and especially the change that Israel, my native country, is going through. It is hard to believe and devastating to follow the last two years, seeing how various long term underground processes and the 57 years long state of occupation are erupting, forcibly melting the last remaining vestiges of a culture which had some hope for peace and some ability for empathy into the darkness of ferocity and brutality to the degree of ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians under the guise of religion. This forced thawing of a democratic society into a theocracy under the guise of the Jewish divinity (and supremacy) is deeply painful to any person who believes in humanity.

However, this is not a political piece. It comes from pain; it attempts to find a way to digest the incomprehensible ongoing in order to maintain some sanity.

Chaya Czernowin

CHAYA CZERNOWIN ON GALINA USTWOLSKAJA’S 2. SYMPHONY

The first time that I heard the Second Symphony, it was for me a real point. The piece has a crazy orchestration, six flutes, six oboes, six trumpets, and then some lower instruments. My new piece, The Divine Thawing of the Core, that’s the weird name, is very strongly related to the Second Symphony in terms of orchestration.

⚛️

When I heard this piece for the first time, I knew its importance in general, but especially for myself. It really touched me very deeply. And it didn’t touch like music. It touched me like a lived experience. It’s like when you are scourged or when you get burned. It was a real physical experience. And I knew that this is going to be an important piece for me. And then in 2018, I was the curator of the “Fromm Concert” at Harvard University, and I brought that piece to a live performance. And so we had groups of six plus trombone, tuba, piano, percussion. Everybody who was in the hall felt that it was not music on the frequency that we know. I heard that piece on YouTube before, but then, when I heard it live, God, it had such a powerful impact.

⚛️

She’s not a woman composer. She’s more male than any male composer. There is no femininity.

⚛️

The oboe is the most oboe it can be. She is not subverting the instruments. She is not extending them. No, it’s going back to the real essence of what this instrument is: what is special about this instrument? What is the oboe opposed to the bassoon, even if it’s a brother. What I feel in Ustvolskaya in relation to Varèse: Varèse is constantly on a search. It’s the spirit of a search. Ustvolskaya actually: is she searching? No, she’s not. She’s talking from a place where she is speaking more like a prophet. She is speaking destiny. Is a prophet looking for the words to say? The prophet knows, in a way. I have to say, just as a small bracket, that this is for me a point of distance from her, because sometimes her absolutism scares me.

⚛️

But with all its strangeness and idiosyncrasy, it’s not talking about her whims of interventions. It’s talking about something absolute that she is letting shine through her work.

⚛️

It is the non-involvement of the human element. Music is allowed to be itself without the composer wanting to prove something or put something that is coming directly from their personal humanity. It is the ability, a genius ability, that the composer can develop not to intervene in their material and to be able to let the material speak through them in the best and most coherent way. And that is for me what is connecting Ustvolskaya and Feldman.

⚛️

And the doubling of the same instrument: it’s not one soloist, it’s not identifiable and recognizable. We can’t identify with it. Suddenly, the human is speaking through the oboe. No, it’s the soul of the oboe, in the six or four or three oboes. It really needs to be that width or weight for that instrument to express itself this way. She opens a huge field in which she can move. That field is able to carry it because it is wide open.

taken from the conversation between Chaya Czernowin and Rebecca Saunders in the program book of Darmstadt Summer Course 2005