READER: CHROMA

02.08.2025

Rebecca Saunders: Chroma I–XXII (2003–25)

New Version for the Darmstadt Summer Course

Carl Rosman (Clarinet)

Michele Marelli (Clarinet)

Marco Blaauw (Trumpet)

Lucy Humphris (Trumpet)

Jürgen Kruse (Piano)

Ernst Surberg (Piano)

Dirk Rothbrust (Percussion)

Rie Watanabe (Percussion)

Yaron Deutsch (Electric Guitar)

Hannah Weirich (Violin)

Sara Cubarsi (Violin)

Dirk Wietheger (Cello)

Florentin Ginot (Double Bass)

John Eckhardt (Double Bass)

Rebecca Saunders (Composition and Arrangement)

Christopher Collings (Assistance)

Brilliant, gorgeous, painted, gay,

Vivid, flaunting, tearaway,

Glowing, flaring, lurid, loud,

Screaming, shrieking, marching, proud,

Mellow, matching, deep and sombre,

Pastel, sober, dead and dull,

Constant, colourful, chromatic,

Party-coloured and prismatic,

Kaleidoscopic, variegated,

Tattooed, dyed, illuminated,

Daub and scumblc, dip and dye,

High-keyed colour, colour lie.

–– Motto from “CHROMA. A Book of Colour” by Derek Jarman, an inspiration for Rebecca Saunders’ piece.

REBECCA SAUNDERS CHROMA

It is not easy to describe the happiness which one encounters while, together with a small ensemble, awaiting the entry of the next instrument. The music is, for a long time, somewhere else. In the distance, a bass drum rears up theatrically. Two double basses loop up to heights at which they become fragile, seeming to lament their inability to produce a singing, cantabile line. The sound reverberates for a long time in the nooks and crannies of the room until it reaches my ear. All this occurs in the distance; here, a sort of busy quietness and relaxed concentration hold sway. Listening. Orienting. Decoding. Waiting. A chair creaks. Someone breathes heavily. Two trouser legs scrape against one another. The musicians near me caress their instruments, moisten the mouthpiece, warm the fingerboard, caress the bow hair, while the time stretches out until the next entry.

Perhaps I wasn’t supposed simply to sit. Like the bulk of the audience, I too might have followed the music’s path and moved to a new position with every beginning of a new piece. Yet one is free to reject the path the music superficially seems to take, and it is in this that something remarkable happens: as a listener one can choose to locate the music on the periphery, without this signalling any sort of diminishment in aesthetic terms or a failure to give it the attention it deserves. Instead, space and distance become specific, aesthetic parameters of the experience. Counterpoint acquires a new spatial, architectonic dimension. Normally, it is the composer who determines what is in the foreground and what in the background, whether this has to do with a melody and its accompaniment, or using more elaborate devices, like an off-stage orchestra. Here, though, it is the listener who is responsible for arranging the material, creating new perspectives with each fresh performance. With this comes a huge luxury, which feels almost profligate: the listener can remove themselves to the background, hearing the music as if from the wings.

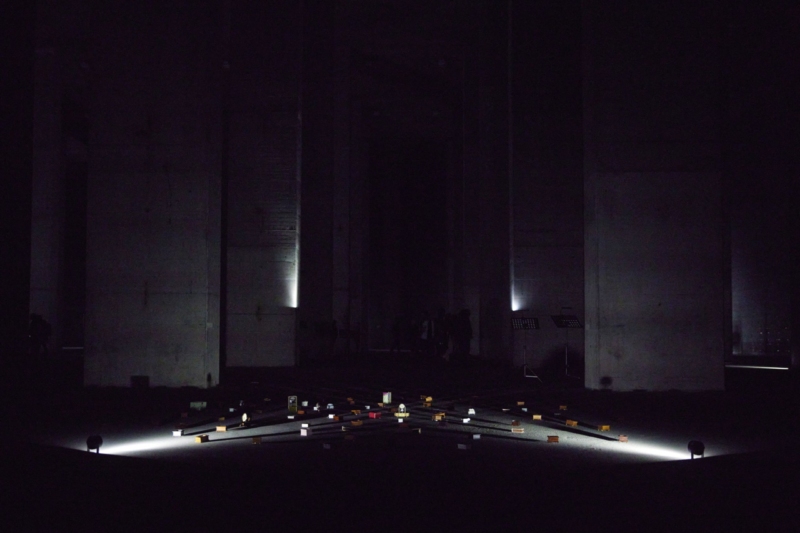

“Mix the music with your feet” was the advice of Tate Modern to listeners, when Rebecca Saunders’s chroma was premiered in the gigantic turbine hall there in 2003. The formulation may appear a little prosaic, but the idea of ‘mixing with your feet’ shows what lies at the heart of the piece. For chroma, Saunders developed a set of chamber miniatures (though some are larger than that might suggest) – from solo to trio –, which are arranged both across time and across space as a sort of collage. In the original version from 2003, there was a piano, duos for two violins, two double basses, and clarinet and trumpet, as well as the two ‘axes’ of the work, around which the work as a whole is arranged: trios for piano and two percussionists, and for clarinet, electric guitar and ‘cello. Since then the collage has been expanded to a total of twenty modules including duos for tubular bells, clarinets, e-guitar and musicbox, double-bell trumpets, and solos for a korg electric organ and crotales, among others. Added to these instruments is a range of sonic objects: a cluster of 117 musical boxes, with which Saunders evokes a sort of ‘doll’s house nostalgia’, and the ancient-seeming pops and crackles of a 78rpm recording of a melancholy Norwegian folk song, which came into her hands from a Stockholm junk dealer.

Chroma is bound up with various traditions, insofar as it can truly be classified using existing genres. It is spatial music, but not really in the sense that might normally be meant by the expression. Unlike Stockhausen’s Gruppen, Xenakis’s Terretektorh, or Boulez’s Repons, Saunders does not create an artificial musical space, hollowed out within the real, architectonic space. Instead the performance is, as it were, ‘nested’ in a space, the music exploring that space like a sort of echolocation. In Saunders’s music, then, the space, too, is fragmented, or as Bastien Gallet once put it ‘decomposed’. For Saunders, space becomes a flexible parameter. “The real subject of the piece, ” she explains, “is density. How much music can a space tolerate? When is it saturated? How do I create transparency? Where is there a space for silence?”

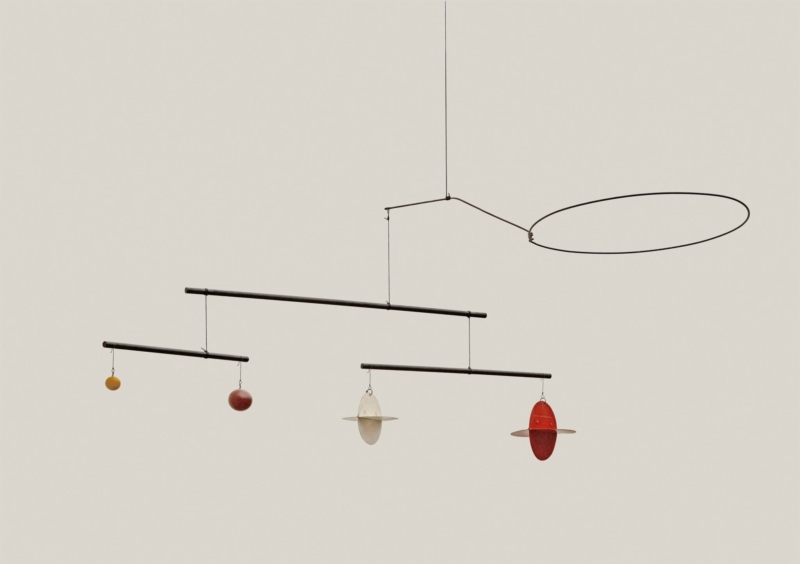

A further work category with which chroma is concerned is the ‘promenade concert’, given credibility within the avant-garde, again, by Stockhausen in his 1968 Darmstadt performance, Musik für ein Haus. Yet Saunders is interested neither in the central idea of the ‘promenade concert’ – a tour of a musical museum exhibtion, with the audience genuinely, physically ‘on the move’ –, nor is it for her a question of several different works occurring at the same time, their intersections governed, more or less, by chance. That is to say, Saunders has not only coordinated the characteristics and patterning of the individual miniatures with one other, but has composed each in view of the whole. At the heart of the piece is a formal framework which allots the individual miniatures a particular position and which guarantees that the brief moments in which events cut across the various ensemble groupings will occur. This formal scheme is, to be sure, reworked for each new performance, not least in order to take into account the particulars of the performance venue. Thus, the synchronisation of the individual parts of the whole work can be varied, since, too, the addition of each new piece – the seven numbers of the original version have grown in the meantime to twenty – thickens the sonic space and shifts the temporal proportions. This formal scheme distinguishes chroma from a musical mobile, like those developed by Haubenstock-Ramati and Boulez, with individual sections which may be exchanged with one another, although the sorts of changes of perspective of the listeners in Saunders are naturally reminiscent of the motions of Calder mobiles.

Saunders’s chroma, then, is neither spatial music, nor ‘promenade concert’, nor even really ‘mobile’, but is, first and foremost, collage. Discrete, independent materials are, in this way, placed against, alongside, and above one another, such that in combination something new comes into being, which is not present in any of the individual pieces. Saunders calls the individual miniatures ‘sound surfaces’ to make clear that depth, space, and context can only develop as a consequence of the interleaving of and confrontation between these surfaces.

The work’s title, chroma, refers to a clearly distinguishable and nameable colour, but one which is distant from other colours. Saunders has emphasised that the individual ‘sound surfaces’ must be distinguishable. This is true for timbre and register, but also for compositional focus: the clarinet and the trumpet rub up against one another harmonically; the piano moves toward pitchlessness with high, choked hammering. Some pieces, such as the trio for clarinet, electric guitar, and ‘cello, remain entirely autonomous. Other numbers resemble small scenes. The second of the two double bass duets, performed at a distance from the public on slack, detuned strings, flanked almost perfunctorily by the piano, has been described by the composer as being “like late in the evening, in a bar”. The individual groups are themselves, then, internally unified, both musically and thematically. The spatial disposition of the instruments is sometimes at odds with this, though. It can happen that the instruments of a group operate “as widely set apart as possible”, as is the case in the trio for piano and two percussionists.

The diversification of individual ‘sound surfaces’ is one subject; the composer’s writing is another. Saunders has a developed, laconic style at her command, in which each note is recognizably her own (a feature which is, surprisingly, no less true of the ‘foreign bodies’ in the work, such as the musical boxes and the record player). The stylistic, conceptual, and aesthetic unity of the work is thus not up for debate. Saunders explains that chroma subsumes the creative phase of 2003–2005 and that the materials developed in these years can easily be combined with one another, even if individual pieces, like the violin or clarinet duos (2006 and 2007, respectively) came about later. Furthermore, chroma marks a sort of turning point, in so far as the idea of sound surfaces, which can be variably combined with one another, has been adopted in several other works, such as stirrings still (2006), Company (2008) or murmurs (2009).

In this context, precisely as a consequence of the relative independence of the individual numbers – which often resemble studies or snapshots, in themselves brittle, inchoate, unstable or grainy – the listeners find themselves placed in a perhaps unexpected isolation. At close range, the individual numbers seem separate, to a certain degree estranged, from one another. The way in which Saunders imbues the individual ‘sound surfaces’ with an ‘object-character’ certainly contributes to this impression. Above all, the way in which the groups are dispersed through the performance space and the distance between individual tones subject the listener to an impression, barely graspable in its entirety, of a moment of existential separation. Perhaps this finds its most drastic expression in the experience of someone who has, together with a small ensemble, waited for the entry of the next instrument…

Björn Gottstein, tr. Martin Iddon