READER: OTTETTO

29.07.2025

Riccardo Nova: Ottetto (2012) – 19’

for four saxophones, four percussionists and electronics

Participants of the Percussion Studio

Jeong Hyun Hwang

Keith Ng

Aditya Bhat

Jieru Ma

Participants of the Saxophone Studio

Kyle Hutchins (Soprano Saxophone)

Robert Burton (Alto Saxophone)

Paula Soriano Ibáñez (Tenor Saxophone)

María Luisa Cuenca Arraez (Baritone Saxophone)

Håkon Stene (Musikalische Leitung, Percussion Studio)

Jennifer Torrence (Percussion Studio)

Patrick Stadler (Saxophon Studio)

OTTETTO

Ottetto is a meditation on breathing in and out (pranam), a slow oscillation between two states, a hypnotic recurring movement that can speed up, slow down or remain constant. Cyclically a more or less obvious change emerges, a new direction, a question, followed by an answer if possible, or simply a second question. I have used a complex metrical structure, a kind of invisible ‘dēmiurgòs’, a relentless organizing force. In the Vedic tradition, a (poetic) meter was considered a precious gift, a tool that could be used to achieve a goal, or even a weapon of destruction.

This piece was commissioned by BL!NDMAN and is dedicated to BL!NDMAN.

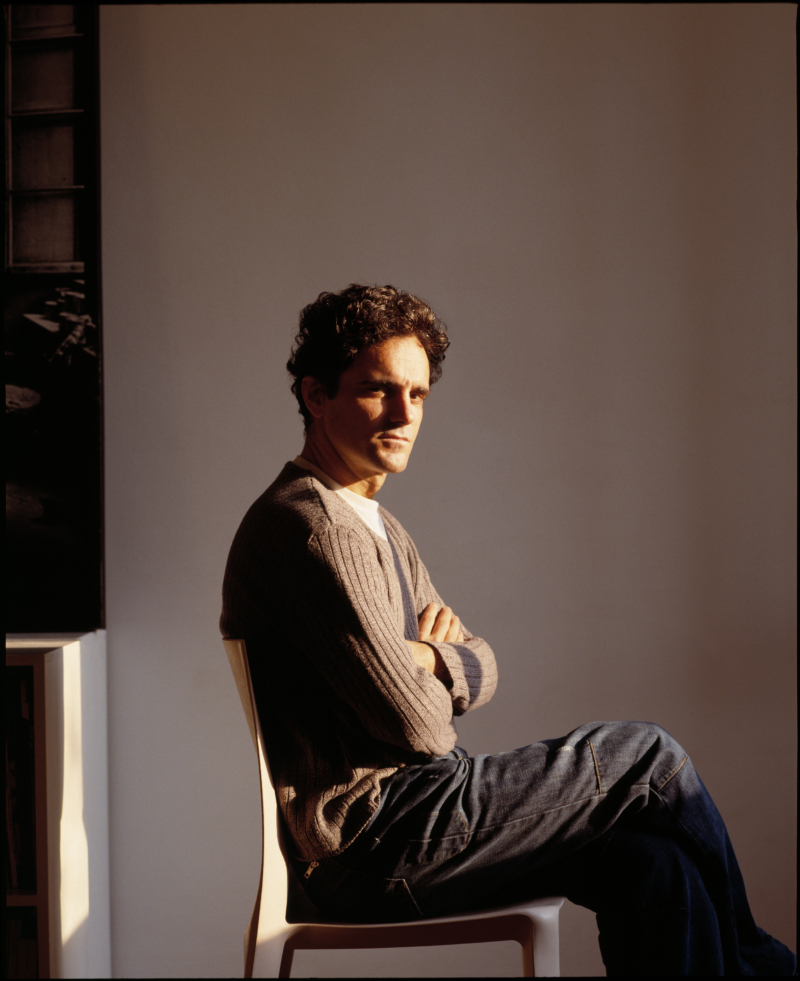

Riccardo Nova

RICCARDO NOVA IM INTERVIEW

KL: The work we are hearing tomorrow is Ottetto for two quartets. You told me, that you were in India during the time of composition. Where have you been in India and how was this reflected in this piece?

I lived in South India for eight years actually. When I finished my Conservatory and the academic studies in Italy in the early 90s, I went to India. I was interested in South Indian music because of the rhythmical aspect of music. So I went there every year for three or four months, living with a family of musicians. After several years practicing Mridangams, which is a South Indian double head percussion instrument, I started working with Indian musicians and ensembles. So I decided to live there to continue studying Indian music. Ottetto was in this period, where I had my house in Mysore in South India. That is in Karnataka, close to Bangalore.

KL: What can we expect from Ottetto and what are some things you connect to it?

It is an older piece, from 2012 and it is constructed within a rhythmical cycle which is repeating itself from the beginning until the end. So whatever happens is related to this time cycle. There are some hierarchical points in this rhythmical cycle, where you hear stronger accents. So everything is related to this cycle which in Indian music is called „Tala“, that means „meter“ or „cycle“. It is an amount of time which repeats. The cycle of this piece is a 19-beat cycle that repeats itself from beginning to end in different BPM.

All the harmonics, the chords and everything are in just intonation. I have been working a lot with harmonics from the saxophones and did a lot of pre-recording of the material with harmonics, edited them and put them together. So the electronics basically is built with natural harmonics from different fundamentals from the saxophones.

KL: What has interested you in this instrumentation of a saxophone quartet in the first place?

It’s interesting because it’s a mono colour ensemble. In terms of the harmonic spectrum and things like that, it works very well because the sound belongs to the same timbral family. I was looking for the spectral colours, so this was fascinating. Also especially the Baritone-Saxophone can produce a lot of harmonics. I think I’ve used up to the 17th harmonics, so there’s lots of natural harmonic possibilities on different fundamentals. I experimented a lot with this harmonic spectrums in the quartet.

KL: And the percussion part? What role does it have in this sound world?

The Percussion part plays more the underlining rhythmical role. Usually, I try to convert the harmonic aspects of music into horizontal rhythmical patterns. Because rhythm is a kind of slow interval. If I think of the relation 2:3, I immediately recall the interval of a Fifth, a Tritone is 5:7, and so on. I immediately try to convert all harmonic aspects into rhythmical aspects, so actually the rhythmical structure is a kind of conversion of the vertical aspects. I’m trying to do this more and more and this piece was really at the beginning of this research.

KL: You mentioned in some texts about the piece, that this rhythmic dimension – which is very important in Indian music generally – has a special connotation for you, because meter and rhythm are of specific importance also in the Vedic background.

Yes. I have always been very much interested in the rhythmical aspects. I remember when I was maybe 10 years old in the primary school, I went to a concert and there was a tabla player and Indian musician – I was shocked by the rhythmical virtuosity of this music! When I started studying Indian music more deeply, also through studying Messiaen, after the Conservatory it was kind of natural for me to go to India.

I started practicing South Indian music for a few years and because I was living in this family of Brahmins, we were reciting Vedas all the time. I noticed also the Vedas being very interesting rhythmically. Everything is metric, there are very strict rules to recite them and there are mnemonic techniques to make permutations of this chant. It really is related to middle-ages counterpoint, not in the harmonic dimension, but in the time dimension. It is really like combinatorics, a system similar to what in the Western music happened in the vertical dimension.

I was interested in this mnemonic technique. Actually the Indian music is a purely oral tradition that is focused on developing a strong memory. They don’t use the eyes because they don’t read music. They only use the ear and have these mnemonic techniques. So it’s a kind of complementary universe to Western music, where the eyes are a very important tool. We start learning music by reading, and even if we memorize music, we use a kind of visual memorization.

That doesn’t exist in Indian music, it’s all based on the ear and memory. And the metrics help the memory a lot. In Western music, the metric is gone because we don’t need it anymore. The memory is all in writing, we transcribe everything and it’s kind of a hard disk. It’s outside of our mind.

KL: It is oral versus written tradition. Especially in later works, you have been trying to combine these two traditions. Your opera project Mahābhārata, after the great ancient epic text by the same name, for example – which was realized in part with ensemble Musikfabrik – also involves Carnatic musicians. So for them, a written score is probably quite challenging.

It’s quite the challenge and it is a long process. The South Indian musicians that were involved with Musikfabrik, I know them for many years – I met the vocalist first, when she was three years old and the percussionist when he was a teenager. So it was a long process and now they also use the eyes because they have developed a writing technique, actually their own notation. I spent a lot of time dictating all the music to them for them to transcribe it into their notation. But they use the script to recall something which they already know. They see it, then they recall it, the muscle memory comes back immediately. If they see the script, it is not like a different way of reading music.

KL: And in the case of Ottetto, it was probably the other way around – you have been working together with two quartets of the BL!NDMAN ensemble.

Yes, it is a big ensemble based in Belgium.

KL: When you presented the score to them, which was influenced by these Indian rhythms, which learning process did it need on their side to get accustomed to 19-beats rhythms for instance?

They are not really traditional Indian rhythms, but they are connected to this cyclic view of the South Indian music. In the South Indian music there are different shapes, like what they call „the cow tail“ which goes from big to small or the contrary from small to big. There are several shapes which I applied in this piece. For instance, there is a section which goes from 19 beats to one beat, so it’s a kind of rhythmical acceleration. It’s not easy to learn it. It’s easier if you don’t read the music, actually, because when you have it all in your muscle memory it becomes very natural.

Also in the experience with Ensemble Musikfabrik, in the beginning they said „No, that’s impossible to do.“ But after practicing and because they had the example of the Indian musicians that could do it easily – after practicing, it becomes natural also for the Musikfabrik musicians.

KL: These relations of numbers, are they also connected to some symbolic meaning through Vedic backgrounds, for example?

Numbers in Vedic tradition are very important. Each meter is connected to a God. For instance, Rudra has an 11 syllabus meter related to him. Also, there are very important mantras that are only a kind of sequence of numbers. There is a very important one in the last collection of the Rudra mantra, which is just a series of odd numbers until 33, then only multiples of four and so on. There are these strange sequences of numbers and I have used these to create harmonies in the opera piece with Ensemble Musikfabrik, actually.

But numbers are also very important in Indian music generally because you communicate with the musician through numbers. At the very beginning, they learn to count – every kind of a number, odd and even numbers with a sequence of syllables.

KL: Do you see your music as a sort of other form of these religious and cultural aspects that you have been getting to know in India?

Not exactly, but of course it is a connection between these two traditions, the written tradition of Western music with all the possibilities that it gives to you: if you write something down, you have huge possibilities in harmony orchestration, you can work with a lot of instruments. On the other side there is this oral tradition which has developed these huge mnemonic techniques and this combinatory techniques, because it is basically a soloist music. They have been free to develop the rhythmical aspects much more than in Western music because they are not obliged to the verticality of the music.

The Vedic tradition is so much concerned with rhythmical aspects, because Sanskrit is still a language which retained a quantitative metrics – long and short syllables. So when you speak or recite Sanskrit, it’s already rhythmical language, because you have to be aware that there are syllables that have a three beat value, others with a two beat value, and some with one beat. So if you want to recite precisely, you have to count like a musician and every recitation is music and, actually, a ritual.

KL: Do you want to retain this ritualistic quality in your written works?

Nowadays, whatever I do is related to the Mahābhārata Opera project, which will be a three act opera. So even if I write a small piece, it will be a study, connected to this. I’m digging deep into the Vedic mantras and the Sanskrit text of the Mahābhārata. So I work a lot with vocal music and the Sanskrit metric is guiding me. It already has a very strict metrical pattern embedded within it and I’m following it. I’m trying to lose my ego in these texts to make them speak. I am not trying to express myself, but to let the music come out of the mantras and texts themselves.

Questions: Karl Ludwig