READER: SCENES FOR ORCHESTRA

19.08.2023

Morton Feldman: String Quartet and Orchestra (1973) – 22′

Mariam Rezaei & Matthew Shlomowitz:

Six scenes for turntables and orchestra (2023) World Premiere – 20′

Scene 1: The First Scene

Scene 2: Screech (recit.)

Scene 3: Organ Tones

Scene 4: Milford Graves in heaven

Scene 5: Beat juggle shuttle

Scene 6: Harp Whip (recit. and chorus)

Commissioned by the Darmstadt Summer Course, Ictus, deSingel, Brussels Philharmonic and nyMusikk

PAUSE

Kaija Saariaho: Orion (2002) – 25′

for orchestra

I. Memento mori

II. Winter Sky

III. Hunter

Mariam Rezaei (Turntables)

Fabrik Quartet

Federico Ceppetelli, Adam Woodward (Violin)

Jacobo Diaz Robledillo (Viola)

Elena Cappelletti (Cello)

hr-Sinfonieorchester

Pierre Bleuse (Musical Direction)

With the kind support of Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung

The concerts of the Frankfurt Radio Symphony at the Darmstadt Summer Course are regular highlights – as it will be this year, when the orchestra plays the final concert under the direction of Pierre Bleuse, the new musical director of the Paris-based Ensemble intercontemporain. In Darmstadt, the orchestra is able to realize programs that would be difficult to promote in the rest of the season – this is probably even more true for the Scenes for Turntables and Orchestra, created collaboratively by Mariam Rezaei and Matthew Shlomowitz, than for Morton Feldman’s String Quartet and Orchestra. The solo part in this twenty-minute meditative, flowing sound structure is performed by the young Fabrik Quartet from Frankfurt, whose members are in the final stages of their studies at the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts, but have already won several prizes. The four are also participants of the Darmstadt Summer Course this year. The powerful last piece of the evening is full of contrasts: lamenting memento mori – clear winter sky – frantic chasing. The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho likes to develop her pieces out of images and metaphors; here the composition revolves around the myth and constellation of Orion. Saariaho wrote the monumental work in 2002 for the Cleveland Orchestra. Even a good twenty years later, Orion has lost none of its magical power – a grandiose finale to the festival program of the Darmstadt Summer Course 2023.

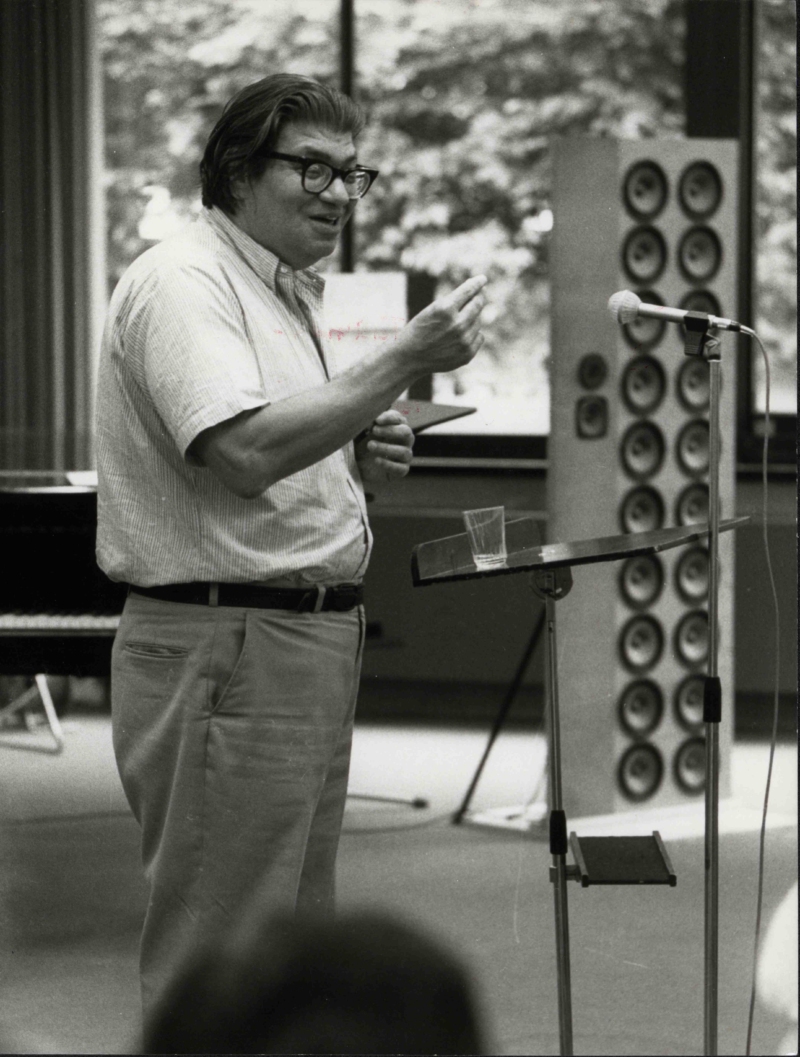

MORTON FELDMAN: STRING QUARTET AND ORCHESTRA

The American composer Morton Feldman was a tall man of sturdy build, a heavy smoker and a friend of clear and loud words. Music, on the other hand, he approached with almost tender restraint. When Stockhausen once asked him for his secret, Feldman advised him to simply leave the sounds in peace: “Don’t push the sounds!”

Indeed, Feldman‘s sounds are not drawn anywhere. They rest in space, breathing in and out. Feldman’s music does not appeal or cajole; rather, it throws its listeners completely back on themselves.

Christoph Becher

In String Quartet and Orchestra, brief lyrical fragments from the string quartet interact with static chords in the orchestra. As in Ligeti‘s texture-based orchestral works, no momentary configuration overstays its welcome. A brief solo cello figure, a repeated descending semitone, is quickly replaced by a sustained woodwind cluster. But in contrast to Ligeti, the replaced figure is not gone for ever: a minute later the descending semitone figure reappears in a much higher register in the violin, this time accompanied by one of the cluster’s pitches sustained on trumpet, before vanishing in the resonance of a piano chord. If in the smallness of the gestures along with the inexhaustible permutation the music recalls Webern, it is in slow motion and stretched over a vast canvas.

Liam Cagney

MARIAM REZAEI & MATTHEW SHLOMOWITZ:

SIX SCENES FOR TURNTABLES AND ORCHESTRA

Interview: Sophie Emilie Beha

Normally, a piece is composed by “only” one composer – how did you manage this cooperative composing?

Matthew Shlomowitz:

I had a role, which is to make the music for the orchestra. And Mariam had a role which was to make her part. But we composed it together, so she would send me a clip of her improvising on the turntables or something she made, and I would send her some orchestral music and she’d make a part to go with it. And then we just would meet every Friday on a video call and have a chat about what to do and how it should start and what should come next. And then in June, I spent three days with her in Newcastle, where she lives in the north of England, and we just put it all together.

How did you interlink Mariam‘s and Matthew’s parts which each other?

MS: Sometimes there was a logic to it and sometimes totally no logic. Mariam once she said: “Oh, I‘ve got this idea for something really mental, like aggressive and crazy – can you make some twinkly Christmas music around?” And so I made some twinkly music and then we put the parts together and both thought: “Wow, it’s weird. You can spend six months trying to write something and then here we just made this thing in a very simple way.” We both like that.

Mariam Rezaei:

Now I‘m 38 and I’ve stopped caring what people think because I‘m very aware that I know what I’m doing, and I‘m doing it in my own way. Writing for the turntable is not about making other people like it. It’s about succeeding with something new and ambitious with a young instrument. So, I fully embrace the experiment of the sound in every possible way. I think sometimes, people’s hesitation comes down to people being scared of the unknown. You can choose to be scared or to be excited.

Mariam, you play an instrument which is likely for surprises. The sound that appears can be very different than you expected. How do you deal with that?

MR: Exactly, you know what the sample is, but you don‘t know what’s going to happen when you play with it. Nine times out of ten, it’s totally different to what I expect (laughs) and I’ve accepted this truth now. Sometimes turntablists tend to have a verystrict idea of how things should sound, but I think that once you start to embrace chance, things get really interesting – to deal with the unknown, publicly on stage, that takes some real guts.

Your composition consists of six scenes for turntable and orchestra. How are they structured, is there an overall narrative or is each of them standing for its own?

MS: These six scenes are all pretty separate. I wouldn‘t say there’s a narrative, but there‘s a kind of arc to it. There’s a shape. We tried to make a kind of journey, I guess in a way, it‘s a bit like Pictures in an exhibition by Modest Mussorgsky or Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta. There are lots of little pieces and they‘re all really separate, but there’s also a reason for an order for them. And for this, we went for the differences. These pieces, they‘re really heterogeneous. After one thing that we want to do, we place the complete opposite next to it. We’re always progressing like this. We want the piece to be like with arms big, wide open to the world.

Interview with the turntablists Mariam Rezaei and Jorge Sánchez-Chiong (PDF, 5.1 MB)

KAIJA SAARIAHO: ORION

Images of the night, dreams, myths, and distant mysteries have always loomed large in Kaija Saariaho‘s work. The Finnish composer’s extensive catalogue contains evocative titles like From the Grammar of Dreams, Wing of the Dream, Caliban’s Dream, For the Moon, Graal Theatre, The Castle of the Soul, and her opera L‘Amour de Loin (’Love from Afar’). Orion, the mysterious and adventurous hunter of Greek mythology, was the mortal son of Neptune (Poseidon), the god of seas. After his death, Orion was placed by Zeus in the sky as a radiant constellation. He is, thus, at once an active (even hyper-active) human being and an immobile heavenly object, and Saariaho has fully exploited that contrast in the present work in three movements – her largest purely symphonic composition to date.

Orion begins its musical journey in a kind of amorphous ‘interstellar space’. The first movement, titled Memento mori (‘Remember that you must die’), evolves from a mysterious introduction towards a powerful orchestral outburst marked by the entrance of the organ. This moment also brings an expansive string melody and an insistent – one would like to say inexorable – rhythmic idea in equal eighth-notes, played fortissimo by the woodwinds. The music then becomes more animated, with a new, exited figure all in rapid sixteenth-notes gradually taking hold of almost the entire orchestra, repeated furioso and con violenza until it is abruptly cut off.

The second movement, Winter Sky, opens with a haunting piccolo solo, continued by solo violin, clarinet, oboe, and muted trumpet. As the orchestral soloists pass the melody around, the other instruments provide a colourful and atmospheric accompaniment. The orchestral texture later fills out with multi-Iayered polyphony, yet the movement remains calm and contemplative. For the ending, the already slow tempo becomes evenslower as the piano emerges from the background with a ‘sky-high’ melody repeating a few notes in changing permutations, over expressive string glissandos and the sound of chimes, bowed vibraphone, and crotales.

We come back to earth with the energetic final movement, titled Hunter. It is a study in perpetual motion – or almost, since the fast motion is repeatedly interrupted by short mysterious episodes in a slow tempo. The third such interruption, more extended than the first two, momentarily recalls the second movement, before the music returns to its former dynamic and joyful self. The excitement grows apace, but as the tempo increases, the volume decreases. More and more instruments drop out, and by the end, Orion has once again assumed his position on the night firmament.

Peter Laki