READER: IMAGINARY LANDSCAPE

19.07.2025

inti figgis-vizueta: To give you form and breath (2019)

John Cage: Imaginary landscape No. 1 (1939)

Alexandre Babel: Snare Counterpoint (2023)

Peter Ablinger: WEISS/WEISSLICH 20 (1992/95)

Zwischen den beiden Konzerten im Orangeriegarten:

Between the two concerts in the Orangerie garden:

Cathy Van Eck: La Nature dans le Miroir (2020)

Romane Bouffioux (Percussion)

Jennifer Torrence (Percussion)

Ane Marthe Sørlien Holen (Percussion)

Corentin Marillier (Percussion)

TO GIVE YOU FORM AND BREATH

Inspired by Joy Harjo’s poem Remember, this piece centers the nature of creation stories in relation to Indigenous identity. Much of native belief and collective knowledge stem from oral traditions and the lens they provide is core to our understanding of the world and the spirits that live with us. To give you form and breath seeks to channel portions of that understanding through ‘ground’ objects and manipulations of rhythm as manipulations of time.

inti figgis-vizueta

IMAGINARY LANDSCAPE NO. 1 (1939)

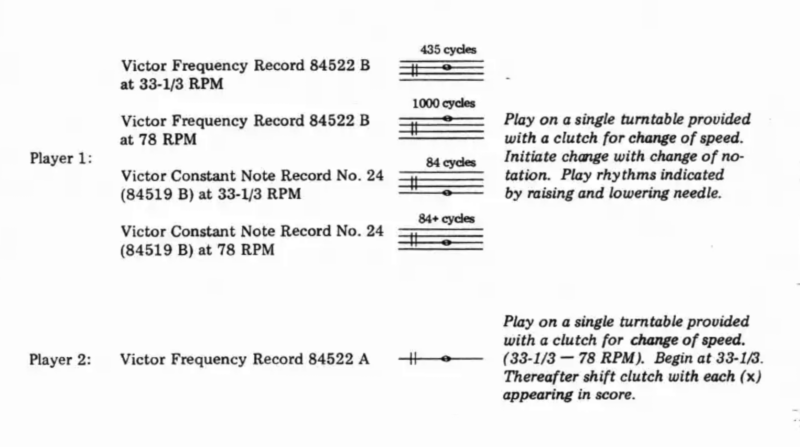

Along with Respighi’s Pini di Roma (1924), which uses pre-recorded bird sounds, this is one of the earliest electro-acoustic works ever composed. Cage calls for a muted piano, large Chinese cymbal, and 2 variable-speed turntables. On the first of the turntables, a Victor frequency record (84522B) and a constant note record (nr. 24) are played; on the second, another Victor frequency record (84522A). This work was premiered in a program together with Cage’s Marriage at the Eiffel Tower.

Cage Trust

SNARE COUNTERPOINT

At the starting point of most of my compositions lies an attempt to reproduce things that I have seen, heard, felt, or perceived. Some of these things can be found in nature, or, like in most cases, are a subjective result of human or non-human interventions.

In the case of Snare Counterpoint, a work that was composed during Covid, I got interested in the idea of information flows and the way they can be structured and framed. This is a very general subject that can be illustrated by many examples, but I remember once witnessing a scene that was particularly representative of this idea.

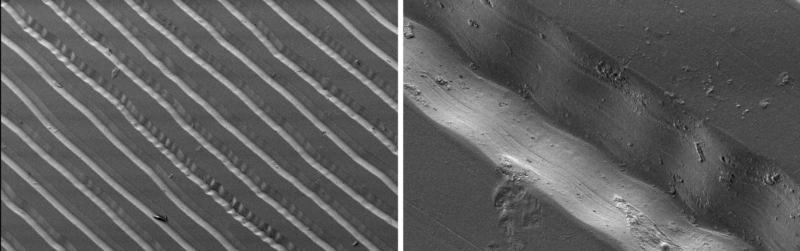

One day in a café, a man sitting next to my table was reading a book written in Braille, the tactile writing system used by blind or visually impaired persons. The book was actually an e-book, and the reading device would consist of an object made out of plastic and obviously electronic components, with a line in the middle consisting of holes partially filled with little dots enabling it to form Braille patterns. The man was sliding his right finger on the line in order to read the text. And when he would reach the end of the line, his left hand would press a button: the line was mechanically disappearing to make place for another Braille pattern. And so on. This process was happening at a rather fast pace, as the man was reading line after line at an impressive speed. His silent gesture was giving visual information about the rhythm of his reading, even though no one apart from him had access to the content of the book.

The stunning thing was the sharpness of the line changes whose regularity produced a clear rhythmic structure. It was almost becoming musical, while obviously not related to the flow of the text.

In Snare Counterpoint, there is a constant and regular rhythmic flow of sixteenth notes from the beginning to the end of the piece, organized in a series of repetitive patterns played by the four percussionists. The flow is structured by discontinuities in the pattern combinations through coordinated starts / stops and changes of patterns. At each pattern change, every percussionist presses a pedal that activates a flash of light to indicate his position in the flow. After watching it and listening to it for a while, a dialog is building between the horizontality of the pattern flow and the verticality of the changes.

Alexandre Babel

WEISS/WEISSLICH 20

a cymbal roll

one or more cymbals (players)

absolutely even

saturated

start and end as abrupt as possible

any duration

WHITE NOISE

Noise is, by definition, the overload par excellence, because noise, white noise, represents the sum of all sounds. At the same time – and as if in a constriction – noise also offers us the exact opposite imposition: the underload. For me, it seems to be the acoustic situation with which we can do even less than with nothing, with silence. If we nevertheless expose ourselves to the noise and listen to it, we begin to hear melodies. We create illusions. And the acoustic illusion is the phenomenon that allows us to catch perception in the act, as it is obvious that it is we ourselves who create it. And what we produce was just as obviously already present in us beforehand. The noise becomes a mirror here, and in the illusion that we find in this mirror, we can expose perception as a self-portrait.

Peter Ablinger from: Kopfhören. Notizen über das Wahrnehmen [Notes on perception]

MusikTexte 124, pp. 13–20, with kind permission.

LA NATURE DANS LE MIRROIR

As a human being I try to observe nature by catching it. I make pictures of beautiful landscapes and recordings of bird sounds. But this process of catching is also transforming nature. I use trails made in the landscape so I can easily walk around, I leave the sound of my footsteps in the surrounding, and by travelling to for example the Ile St Pierre the loud boat sounds are added to the acoustics of the landscape. On a much larger scale, human-caused climate change modifies our environment in general. In a few decades, when the climate at St Pierre is substantially warmer, its nature will have changed also. The wind will probably blow through different trees, in which birds formerly living in more southern regions might live.

Inspired by these possible soundscapes of the future, in my piece nature is caught by a kind of mirror in the performer’s hand. Sensors on their arms are tracking the movements of the mirror. These sensor data are used to develop the sounds for the new soundscape. A loudspeaker placed on the heart of the performers diffuses the composition of this new nature. Every movement with the mirror triggers a sound from the loudspeaker on the performer. In the beginning these are local bird sounds, but they start to transform into non-local bird sounds, the birds who might live here in a few decades. The soundscape develops further in other kinds of artificial weird birds, and other sounds of the environment are added by the movements of the performers. At the end the performers move like birds themselves, and slowly “fly” around with their mirror-arm.

Cathy van Eck