READER: INVISIBLE COLORS

10.08.2023

Olga Neuwirth: Quasare/Pulsare (1995/6)

Brian Ferneyhough: Unsichtbare Farben (1999)

Iannis Xenakis: Dikhthas (1979)

Brice Pauset: Cadenza (2020)

James Dillon: Traumwerk III (2002)

Irvine Arditti (Violin)

Nicolas Hodges (Piano)

Olga Neuwirth: Quasare/Pulsare

Olga Neuwirth’s preference for changing sounds does not stop at the piano, which is rather difficult to manipulate. In Quasare/Pulsare for violin and piano, she juxtaposes it as an equal duo partner with the string instrument, which is easier to influence and already modified in its tuning. By preparing selected strings with materials such as silicone balls and foam, the composer deliberately creates detunings with which she intervenes in the piano sound; through various actions of the pianist, moreover, the interior of the instrument and other components are incorporated into the music. Starting from the sound of a piano string excited by an e-Bow – a kind of pickup that can generate feedback on a metal string through electromagnetic action, the sound quality of which is reminiscent of a sine tone – the formal structure of the piece results from the succession of wavelike sound-space movements of varying density and intensity, which at the end are folded back into the artificial sound quality of the initial tone.

Brian Ferneyhough: Unsichtbare Farben

Commissioned by WDR

I have always been fascinated by the sometimes problematic but always stimulating parallels between musical and non-musical modes of cognition. In the same spirit, the titles of my works are not infrequently selected with a view to throwing at least a little light on the limits and nature of the specific discursive models involved. In many surrealist paintings the title stands in a strikingly fractured or discrepant logical relationship to the image, thereby sensibilising the observer to the unseen presence of a complex field of semantically active energies. According to one of Marcel Duchamp’s most celebrated pronouncements, the title of a painting thus assumes the status of an “invisible colour”, that of the imagination, amplifying and enriching our subliminally speculative perceptions somewhere beyond the limits of the ocularly accessible spectrum. In the case of this short composition for violin it seemed fitting that the various degrees of “invisibility”, absence or erasure involved in the compositional process should be evoked by means of a title itself suffering from radical strategic incertitude at one degree remove.

In a sense, Unsichtbare Farben might be seen as the “tip of the iceberg”, to the extent that the vast preponderance of materials that went into its preparation appears nowhere in the musical phenomenon itself, having been suppressed by a formal filtering operation selecting and interleaving structurally equivalent elements from a relatively large number of through-composed layers.

Correspondingly, the unfolding of the work’s argument is characterised primarily by a series of rhetorical ruptures as short fragments of otherwise impalpable processes are abruptly invoked and, equally suddenly, abandoned.

– Brian Ferneyhough, 1998

“Unsichtbare Farben” (“Invisible Coloros”) is first and foremost a tribute to the brilliant art of the very special violinist Irvine Arditti, to whom this solo piece was composed.

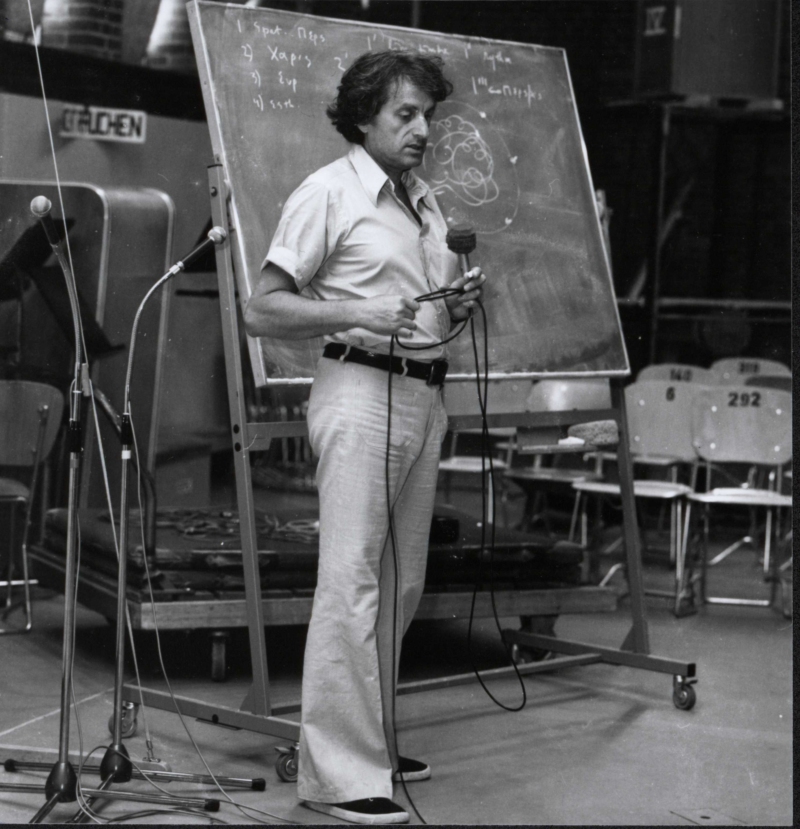

Iannis Xenakis: Dikhthas

Decades after the scandal at the premiere of his first orchestral work Metastaseis in Donaueschingen in 1955, the music of Iannis Xenakis still presents itself to the listener today in confusing dichotomy: The components seem to make up an overabundance of scientific and mathematical formulations. Since the earliest formulations of musical theories by Aristoxenos and Euclid, music and mathematics have been intimately connected. In medieval Europe, the study of music at a university automatically included the subjects of arithmetic, geometry, architecture, and astronomy.

James Dillon: Traumwerk III

Dedicated to Richard Steinitz

Commissioned by BBC 3 for Irvine Arditti und Noriko Kawai

Dillon’s music is full of complexities: a vocabulary that includes complex rhythmic patterns and microtones as commonplace and the requirement of a certain type of acrobatic instrumental virtuosity. The extended set of pieces that forms Traumwerk III exemplifies all these characteristics, as well as a clarity of expression and intellectual rigor that is also typical of Dillon‘s works, which never allow their visceral exuberance to overwhelm their intellectual rigor, a charge that might be leveled against certain effusions of the adherents of the New Complexity. The work was written for Irvine Arditti, with whom Dillon has enjoyed a long collaboration, and Arditti’s particular style of violinistic high-wire act undoubtedly informs the textures of the music.

The title Traumwerk or ‘Dreamwork’ derives from Albrecht Dürer‘s description of his enigmatic and inventively playful ’marginalia’, designed for the prayer book commissioned by the Emperor Maximilian in 1515.

Albrecht DürerWhoever wants to do dreamwork, must mix all things together.

Like the preceding books of Traumwerk, (Book I for two violins, Book II for violin and harpsichord) Book III consists of twelve short pieces ranging in length from a mere 35 seconds (the sixth piece) to 3 minutes (the opening one). Yet while one is dealing with ‘miniatures’; collectively they amount to a substantial, half-hour work. From the start, one is aware of something very characteristic of Dillon‘s work from this period: interlocking ostinati, some regular and others by no means so. At one level, one could imagine these pieces, abstractly, as studies in enigmatic repetition. But what else does that suggest? Surely, spells: Dürer’s age was poised between science and superstition, and there is something hypnotic and ‘uncanny’; (in both the Freudian sense and the normal one) about many of these little pieces that suggest an accumulation of magic incantations.

– Richard Toop, 2008